Glaciers predate human life but our lifestyle causes them to melt. Can a funeral for a glacier get this message across? Let’s do something before it’s too late.

A girl holds a sign that reads ‘pull the emergency brake’ as she attends a ceremony in the area which once was the Okjokull glacier, in Iceland, 18 August 2019. With poetry, moments of silence and political speeches about the urgent need to fight climate change, Icelandic officials, activists and others bade goodbye to the first Icelandic glacier to disappear. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Across the world two billion people — around a quarter of the world’s population — depend on glaciers for water to irrigate fields for agriculture, provide drinking water and to generate electricity.

But these glaciers are melting before our eyes.

Consider that 10% of Iceland is covered by glaciers but that is 1% less than a decade ago. That percentage will continue to decrease as the rate of change due to global warming has become dramatic.

Glaciers are so iconic in Iceland that when one collapses, people hold a funeral.

It’s a ceremony created for humans to make people aware about the urgency of global warming. And it’s a poetic way of marking the end of one of nature’s most inspiring creations.

A land where ice is prized

The first funeral for a glacier took place in 2019. It was for Okjökull glacier, the smallest glacier in a land that is dominated by ice and snow.

Okjökull glacier, popularly known as Ok, was only a modest 15 square kilometres big and had been shrinking for decades. Icelanders regarded diminutive Ok with affection, even making it a character in children’s book.

So the emotional impact of watching Ok vanish was felt not only by the locals who had grown up with the glacier, but across Iceland. Icelanders are brought up learning songs and sagas about their spectacular island. The snowpack of their glaciers creates the wild rolling rivers and massive waterfalls throughout the island before the flow tumbles into the stormy North Atlantic.

Now on the hill which had been covered by Okjökull is a rock with a brass plate with urgent words from Icelandic poet Andri Snær Magnason.

A LETTER TO THE FUTURE

Vatnajökull ice cap and parts of Hofsjökull ice cap, Iceland in September 2022. (Credit: Pierre Markuse via Wikimedia Commons)

Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path.

This monument is to acknowledge that we know

what is happening and what needs to be done.

Only you will know if we did it.

Ice loss in Iceland

Tiny Okjökull was nothing compared to the largest glacier in Iceland — and in Europe — the Vatnajökull ice cap.

Despite its mass, scientists estimate that nine million litres of Vatnajökull’s glacial ice are being turned into water every minute.

The lakes and ice lagoons downstream of Vatnajökull, filled by meltwater, are bigger every year as the glacier itself shrinks.

So should there be funerals for glaciers?

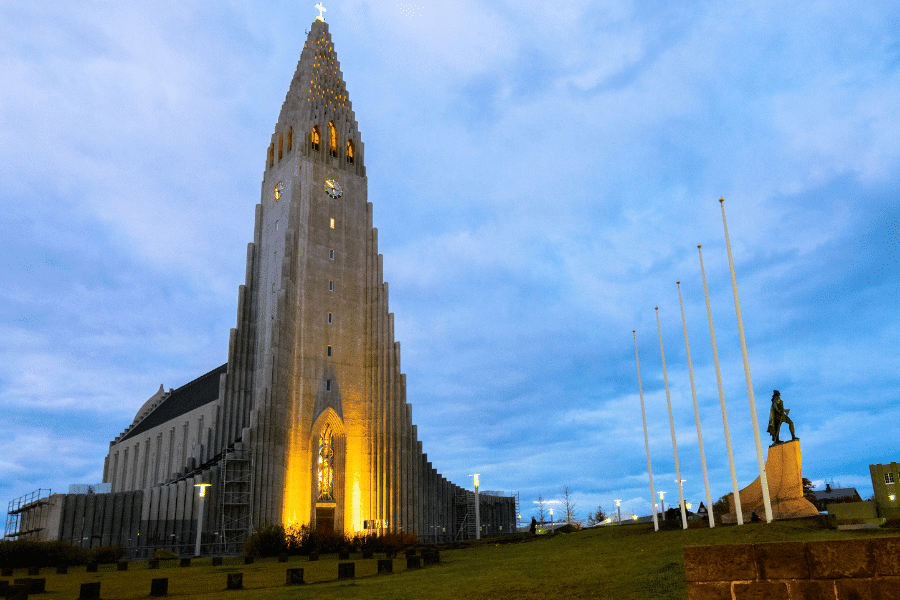

Sigurdur Arni Thordarson, the pastor of Hallgrímskirkja Church in Iceland thinks so. His church was built to resemble the mountains and glaciers of Iceland and dominates the Reykjavík skyline.

“For humans, the loss of a glacier is a real loss,” Thordarson said. “People who have a deep understanding and awareness of interconnectedness of life really feel the necessity of expressing the grief.”

Snow melt in the Alps

It seems a widespread sentiment. A few months after the ceremony in Iceland, hikers, many dressed in black, gathered on Pizol glacier in the Swiss Alps to listen as a priest gave a funeral service.

Another ceremony followed in 2020 for Clark Glacier in Oregon and soon after on a Mexican glacier named Ayoloco by the Aztecs. The Mexican geologists and ecologists who marked the day used the words written by Andri Snær Magnason that commemorate Okjökull.

Crossing into another culture, Buddhists monks in Nepal held an ‘ice funeral’ in the Himalayas in May 2025 for Yala Glacier which had shrunk by two thirds in the past several decades. Attended by locals and climate scientists they gathered under traditional prayer flags across from the last visible ice. Even Yala’s altitude over 5,000 metres was no protection against deglaciation

Two granite stones now mark the spot of the ceremony. One with the words of Magnason from Iceland, the other with an inscription from Nepali poet Manjushree Thapa:

Hallgrímskirkja Church in Reykjavík, Iceland. (Credit: Mattias Hill via Wikimedia Commons)

Yala, where the gods dream high in the mountains, where the cold is divine.

Dream of life in rock, sediment, and snow, in the pulverizing ofice and earth, in meltwater pools the colour of sky.

Dream. Dream of a glacier and the civilizations downstream.

In all these commemorations, Magnason’s alarm from Iceland have been echoed:

…We know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you will know if we did it.

The Third Pole

The glaciers in the Himalayas are sometimes called the ‘Third Pole’ because they account for the most ice after the Arctic and Antarctica.

Around the world glaciers are melting faster than ever recorded but the Himalayas are warming at a higher rate than the global average, up to 65% faster. The Himalaya glaciers feed some of the great rivers of Asia — the Ganges, Indus, Brahmaputra and Yangtze rivers which flow through some of the most populated areas on the planet.

The consequences of disappearing glaciers are starting to be felt. Mexican climate scientists who attended the Ayoloco ceremony pointed out that “without large ice masses on mountain peaks temperatures will increase.”

All of our planet was created by massive geologic forces. Those forces are more easily observable in Iceland, being one of the newest land masses to be created on Earth. It is an island nation that was created by volcanoes but sculpted and defined by glaciers. It may be fitting that, in addition to the first glacier funeral ever held, the first Glacier Graveyard was created in 2024, to mark extinct glaciers and provide a reminder of what is at stake.

The glaciers remembered were taken from the first Global Glacier Casualty List. Soon after, the United Nations declared 2025 the International Year of Glacier Preservation. Now, all fifteen tombstones carved from ice to mark those vanished glaciers have melted.

Questions to consider:

1. Should glaciers, like some rivers which have been granted legal rights, be regarded as living creatures?

2. Does a ceremony like a funeral provide an inspiration for climate activism?

3. What natural formations or environmental places are important to you?

Tira Shubart is a freelance journalist and media trainer based in London. She has produced television news and trained journalists across four continents for international broadcasters, including BBC News, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and Al Jazeera, over several decades.